TUNNEL VISION: Horizon Gallery, (A Utopian-Scale Model)

2020

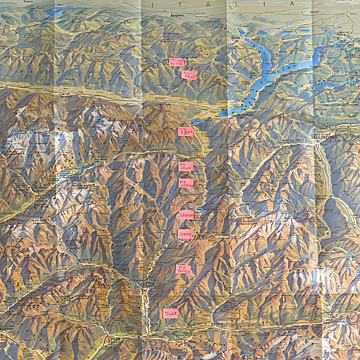

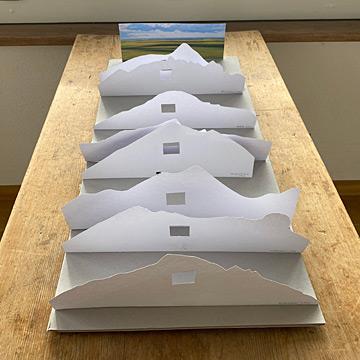

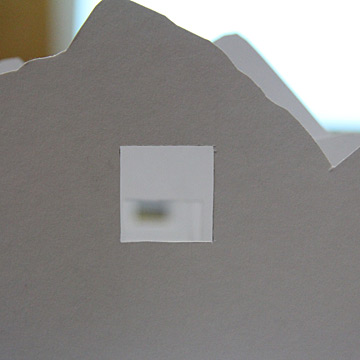

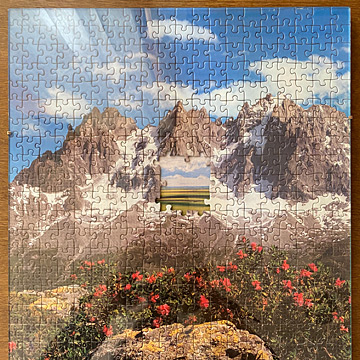

Our proposal is a symbolic tunnel carved through the Alps beginning at Piz Beverin, and continuing across a range of nine mountains between Switzerland and Northern Italy, until reaching the flat open plains of the Pianura Padana. This augmented view is an artistic intervention, creating an imaginary or utopian panorama by linking the landscape across elevations.

For our purposes here, in the Swiss context, landscape is defined by interventions: linguistic, agricultural and infrastructural. The insularity of the Alps provides a unique paradigm to examine these definitions. Switzerland is formed by a series of boundaries and binaries notably in the contemporary context, a straddling of what Rosalind Krauss designates as “the cultural and the natural.”1 The linguistic formation of landscape here is partially defined as a locus where two languages meet. Pastoral politics have also historically shaped the land, specifically the domestication of nonhuman species both animal and vegetal. The original settlers toiled to subsist at altitude, conversely present-day inhabitants are no longer existentially tied to their labor in the land, and in turn tourism is promoted over production.

But this instinct to shape the land extends to the domestication of the mountains themselves. For centuries the Swiss have been tunneling through earth, fighting against inclement weather and geological time. In 1708 “Urnerloch”, the first official tunnel was completed, measuring 64 meters, it provided the original passage over the St Gotthard. The Germanic root of the name Gotthard means divinely stern. A tunnel is also a place where two things meet. The current iteration of the Gotthard tunnel (one of the longest in the world) travels from the Swiss-German canton of Uri to the Italian speaking Ticino. In Italian the word ‘galleria’ and the English word ‘tunnel’ are used interchangeably. The tunnel is a mediation between humans and the land, a space created for travel of people and products, it is a threshold. It also is a symbolic channel between man and nature and a fundamental part of this vernacular landscape.

Switzerland’s natural or geographic insularity embodies an island mentality. These mountains protect and isolate. Nevertheless as languages shift and meld at borders so can ideologies. Our project attempts to expose a new perspective, by using the language of infrastructure as a framing device. We are examining the tunnel as a platonic form, representing progress. We wish to propose a metaphor for mediating this nature/culture bind, by inscribing a path through the materiality of the land itself. Oscar Aldred corroborates this enterprise affirming, “To develop an archaeology of landscape, it is necessary to take a path that weaves not by drawing distinctions that separate past and present, or in bifurcating the sets of relations between the material and body, or between object and subject, but by arguing that people and things are thoroughly entangled along relational paths of signification.”2

This project is impossible for a number of reasons, firstly because Piz Beverin is situated in a protected nature area, and secondly because carving through an entire mountain range for the sole purpose of creating an objectively more interesting view is an absurd gesture. Alternatively, we are proposing either a series of projections which visually “pierce” the landscape, or a series of billboards, one on each mountain, offering the view that will be encountered at the end of the Alpine range. Ultimately, this is a proposition of an infinite horizon by any means necessary.

1 Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” in October, Vol. 8 (Spring, 1979), 30-44.

2 Karl Benediktsson and Katrín Anna Lund, “Time for Fluent Landscapes” in Conversations With Landscape (Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge; 1st Edition, 2016), 62.